HOW TO SIMPLY IDENTIFY A DAMP HOUSE

Buyers of houses, either renovated or unrenovated, should be aware of damp which could cost thousands of dollars in remedial treatment. The presence of damp walls and a damp sub-floor area should not be a deterrent to the purchase of a house as generally it can be rectified. The purchaser should do a little investigation to reduce the risk of unexpected losses due to cover-ups by vendors. A survey by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, Archicentre Advisory Service and the University of Melbourne’s Architecture and Building Department found that 45 per cent of solid brick houses aged 70 years and over, and a quarter of houses aged 50 to 70 years had rising damp [The Age, 1986, p.5].

The rising damp is not confined to solid brick houses as weatherboard houses frequently have rising damp in the brick chimneys. Therefore, the probability of a buyer finding damp in an inner suburban property is high.

Dampness can cause health and associated problems, such as mould, bacteria and airborne infection. Dampness promotes insect attack of timber and causes odour problems. A damp house is a cold house and therefore an expensive house to heat.

Renovators should follow the sequence:

- Fix the roof

- Fix the drainage

- Fix the sub-floor ventilation

- Fix the rising damp

- Re-plaster after drying of the walls and then start renovating.

It is an unfortunate fact that this rarely occurs. Prospective purchasers can follow a simple inspection procedure to identify sources of dampness.

A. OVERVIEW

An overview of the house’s problems can be established by inspection for –

- Water Run Away

- Underfloor Ventilation For Suspended Timber Floors

- Fix the sub-floor ventilation

- Bridging Of Present Damp-Proof Course and Presence of Concrete

- Penetrating Damp

1. Water Run Away

Roof downpipes, spouting and waste pipes should clear water from the site. If stormwater is running into the earth or into spoon drains this is a source of moisture, which could be draining under the house, causing dampness under the floors and deterioration of timber floors.

2. Underfloor Ventilation For Suspended Timber Floors

In wet soil conditions the building needs one double ventilator for every 1.5 m of wall length around the entire building perimeter.

All present vents should be clear. If a building is in a damp area and had insufficient sub-floor ventilation in the past, then the timber floors and stumps could be in poor condition. Terra cotta vents as in Edwardian houses are very poor ventilators and are part of the cause of floor problems in such buildings. (See Figure 1)

Ideally the earth level under the house should be at the same level as the earth outside the walls so that drainage to under the house does not occur. The earth level under the house should be well under floor level to give adequate sub-floor airflow. Inspect the sub-floor area in as many locations-as possible (shine a torch through vents). Should there be a white-cream fungus material growing on the soil or on the bricks then the sub-floor area is very damp. In the worst case, if there is a fruit-like fungus with cotton wool-like strands on woodwork, this is dry rot infection.

Should one be able to inspect the sub-floor area there should be adequate double brick openings in the brickwork below floor level. These should be beneath doorways and within 1-2 m of the corners of each room and every 1.5m along walls. The openings should be near the ground.

A common practice in renovating older buildings is to ignore the need for adequate sub-floor ventilation to existing timber floors and to replace part of the timber floors with concrete. This new concrete blocks sub-floor ventilation to the rest of the timber floors and their lifetime is decreased substantially due to the probability of insect and fungal attack. A particularly suspect area is where the timber floor adjoins the concrete. An additional problem is that the fill under the new concrete may fill over the old damp course or bluestone and cause rising damp in the walls. (See 3 below).

Be aware that if the building has ducted heating installed, the ducts could be blocking the sub-floor space and as such could cause significant floor problems. Hydronic heating would be preferred.

3. Bridging Of Present Damp-Proof Course and Presence of Concrete

In Victorian building the theory of preventing rising damp was that blue-stone which is impermeable to water was used as the footings and a damp course (eg., coal tar, bitumen and sand, or slate) was incorporated in the mortar line directly above it. In the higher value buildings large bluestone pitchers were used as footings and the damp could only come up the mortar lines. However, in poorer buildings bluestone rubble was used and such a large amount of lime mortar was used between the bluestone in the walls that the damp had an easy rise. Once the damp reaches the hand made bricks then rising damp is firmly established. Where the earth level has been raised against bluestone pitcher footings to near the bricks either inside or outside the house, this encourages the rise of the damp in the final mortar lines to the bricks.

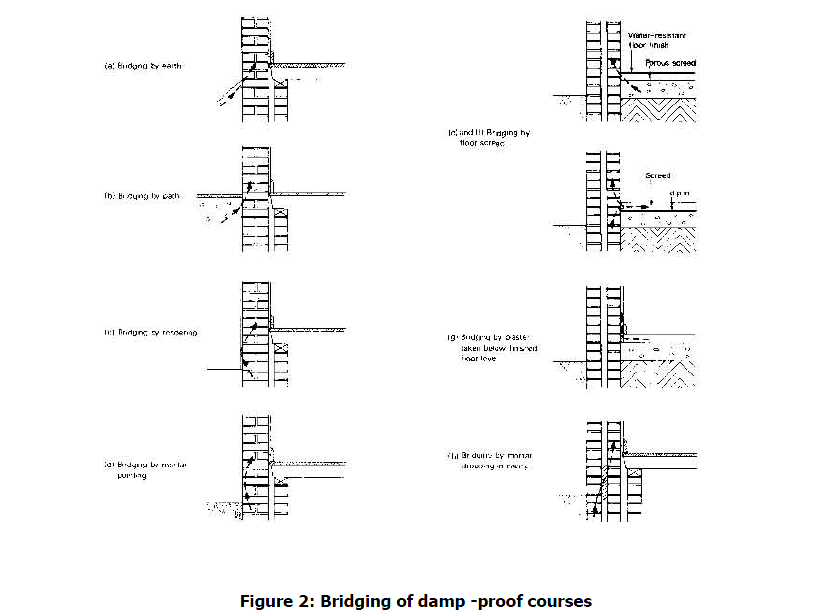

If the bluestone and damp course is bridged then rising damp is the sure result. Bridging could also occur by rendering covering the damp course. (See Figure 2.)

Figure

In Edwardian buildings the damp course, usually bitumen and sand, is normally located at the mortar line level at the top and bottom of the vents. The bitumen and sand damp course is not impermeable to water due to the presence of sand incorporated initially to prevent extrusion of the bitumen. However, it functions in less damp conditions where some damp rises through the first damp course but is mostly stopped by the second (Top) damp-course. Bridging of the bottom damp course, leaving only the top damp course exposed, could be enough to cause significant rising damp.

Concrete present either inside or outside the building may cause problems due to bridging of the damp course by the fill under the concrete. In addition in damp locations the earth under the concrete can become very damp and cause rising damp in the walls where the old damp course in the walls is not sufficiently effective to stop it.

Penetrating Damp

Check for penetrating damp coming through masonry especially on the weather side of the building. Where bricks have been sandblasted this may cause significant penetrating damp due to the poor condition of the mortar lines and the increased permeability of the bricks. This can be solved fairly simply by re-pointing the mortar lines and deep impregnation of the bricks with long life siloxane water repellent.

B. INSPECTION OF THE BUILDING FOR RISING DAMP

There are two cases:

I. unrenovated buildings

II. renovated buildings

I. Unrenovated Buildings

This case, where a building has not been recently decorated, is the easier to survey. The symptoms of dampness, some or all of which may be present, are:

Inside

- Paint does not adhere to the wall.

- Wallpaper lifts.

- Stains appear on the walls.

- Mould spots appear on walls, on clothing, on shoes etc.

- Plaster flakes away, feels soft and spongy, bubbles and white powder or crystals appear (efflorescence).

- Room smells musty.

- Skirting boards and floor boards rot

Outside

- Mortar frets and falls out between bricks and stonework.

- Stains appear.

- White powder appears.

From a distance a darkness at the base of the wall can be seen. A typical sign of Rising Damp is a roughly horizontal tide mark on the wall above which there is little or no damage but below which the paint or plaster has been damaged or the wallpaper is stained or has lifted. Damp usually rises no more than 1-l.5 metres up the walls, although in very damp situations the damage may occur at higher levels.

Move the furniture, which the owner may be using to hide rising damp on the walls.

A low-cost moisture meter can be purchased from reputable building product companies for $79.00. Such devices are useful qualitative tools that indicate the presence of moisture. Care should be exercised in interpreting the readings as the presence of hygroscopic salts always increases readings.

Where waterproof render or plaster has been used in the past to cover up the rising damp, there may be a horizontal line on the plaster above which the damp has risen.

II. Renovated Buildings

The diagnosis of rising damp in buildings where great effort has been taken to cover it up with waterproof render and plaster is very difficult. The only reliable method to detect it is to drive two masonry nails through-the plaster and render into the bricks near the floor and take a qualitative reading on a moisture meter.

This is not normally practicable in a house renovated for sale.

In general waterproof render and plaster is not a solution to rising damp and will fail sooner or later. It is only logical that what is needed is a positive horizontal barrier to stop the rising damp. A vertical waterproof barrier usually forces the damp higher, out of cracks or out at the base of the wall where the skirting boards rot. There are various means of detecting new plasterwork (possibly waterproof) above the skirting boards. These methods are:

- hammer masonry nails into the plaster – waterproof render needs a high cement mix and will be very hard. This may not be practicable on an inspection.

- inspect the wall and look for a join line of old plaster to the new plaster. A join line may mean that a damp course job has been done and replastering has been carried out. Alternatively it may mean that only waterproof plastering has been carried out. Ask the owner about any work completed and request the name of the contractor. Note that there are very few methods of damp course installation that are successful so investigation of the details of the work is necessary.

- tap the plaster with your knuckles and listen to the tone of the wall from above 2 m from the floor down to the wall at the top of the skirting board. A different tone usually indicates new plasterwork carried out above the skirting board. Waterproof render and plaster is a disaster for the buyers who finally retain the problem in the house. They lose the value of the decoration they have paid for in the house purchase price.

The skirting boards may have to be removed and affected plaster eventually replaced after a new damp course has been installed or the basic problem rectified.

In renovated buildings, search for new concrete at the rear of the building or in other areas. Many renovators pour concrete at the rear of a timber floored building and then place prime cost items such as the kitchen and bathroom in this position. The sub-floor ventilation is interfered with and a buyer cannot easily return to satisfactory sub-floor ventilation without large capital loss.

Another trap for buyers is the underlay under the new carpet. In the unrenovated building there were bare tongue and groove floorboards and possibly felt underlay under carpets. In this case damp air from the under floor area came through the floors and floor coverings into the rooms and eased the dampness under the floors. However, if new carpet has been laid in the renovated building without rectifying the sub-floor ventilation and rubber or foam underlay and backed carpet is now sealing the floors, this can cause problems. The timber floors can become very damp in a wet location and experience rapid deterioration.